About the novel: Have Blue Sky will be published on November 11, 2026, by the “Subplot Imprint” of Amplify Publishing Group. The novel traces the journey of four individuals whose interactions with the legendary aircraft will alter the course of their lives.

About this website: This website is a platform where I can share photos of the airplane, of the pilots who flew the F-117, and of the maintenance professionals who kept the plane in the air.

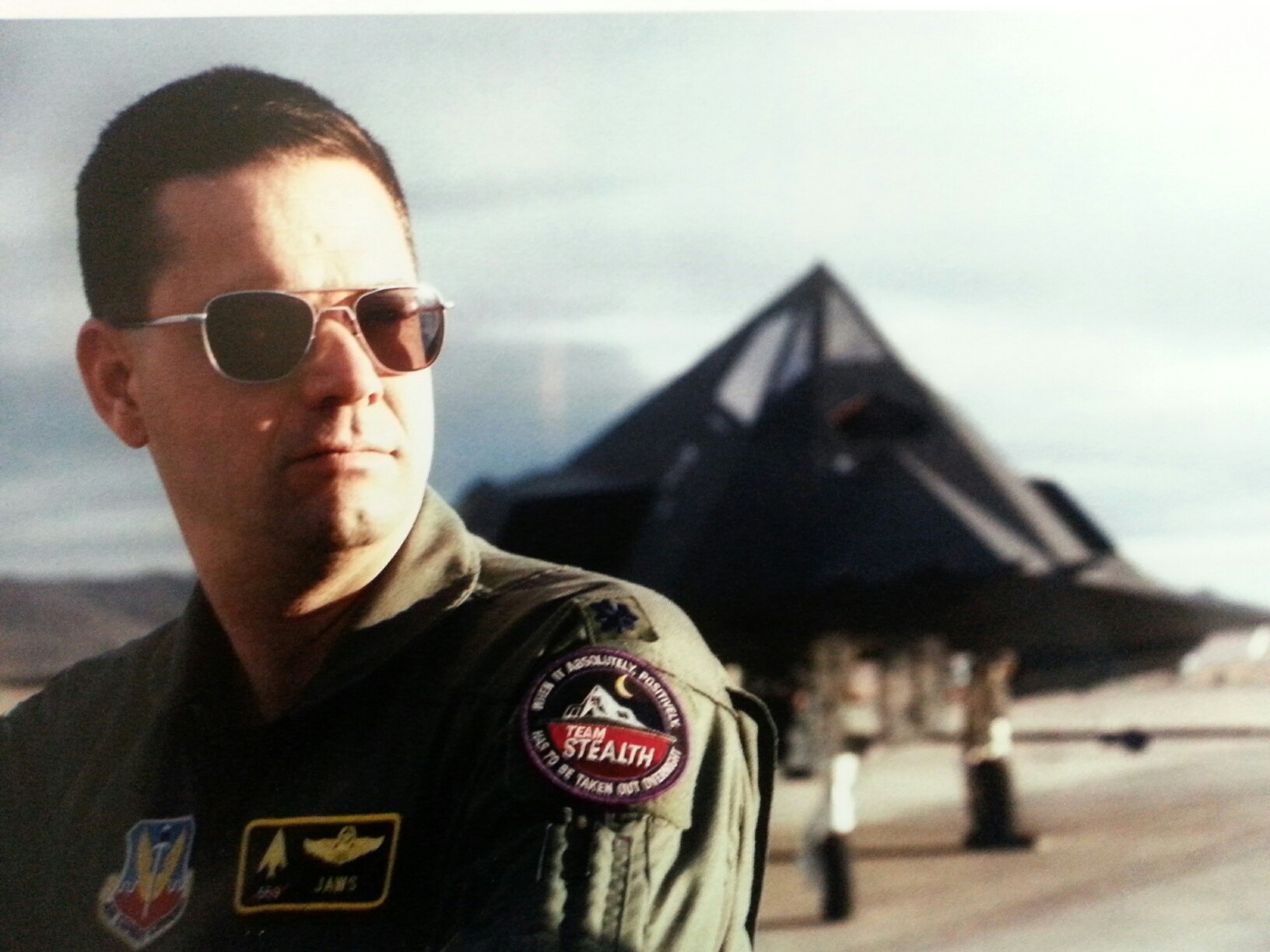

About the author: The pilots who fly the F-117 Stealth Fighter are called “Bandits,” and each pilot who flies the jet receives a “Bandit number” after their first flight. The author of Have Blue Sky is Bandit 534.

As we countdown to the publication date of November 11, 2026, I want to share a few photos with you to help tell the story behind the story of the writing of Have Blue Sky.

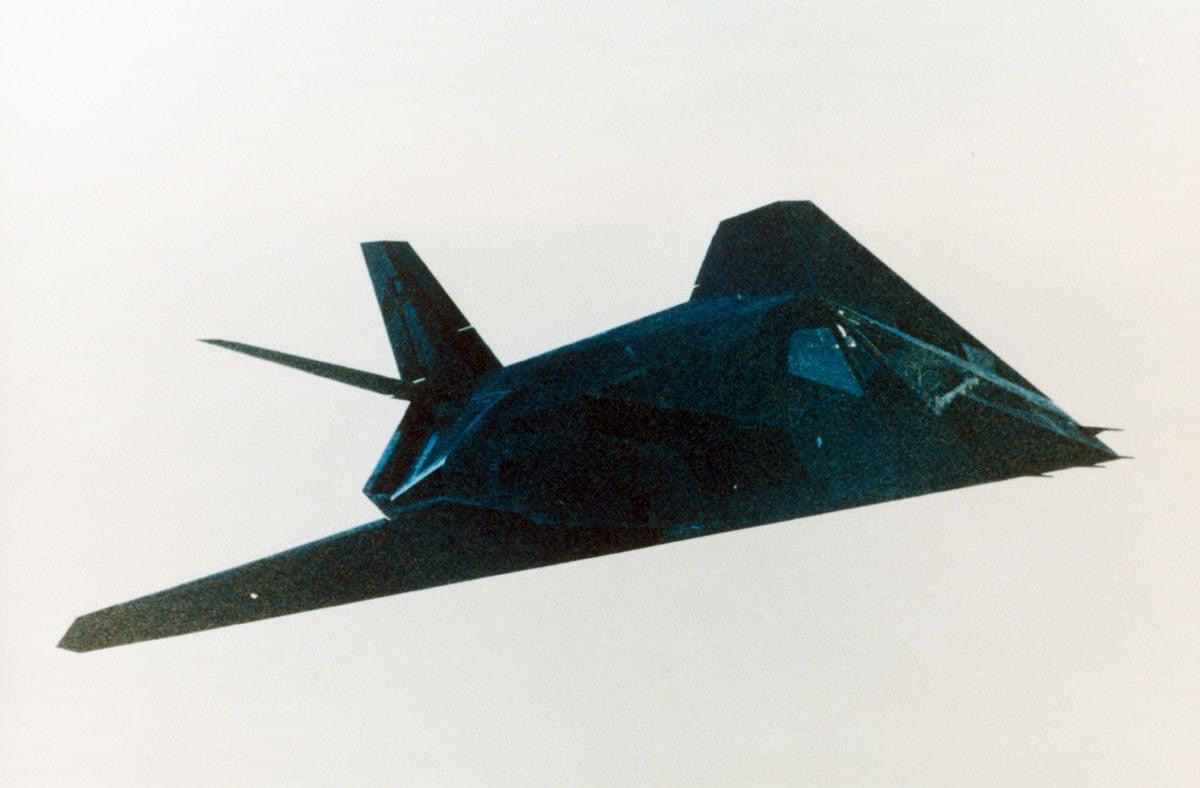

The F-117 Stealth Fighter

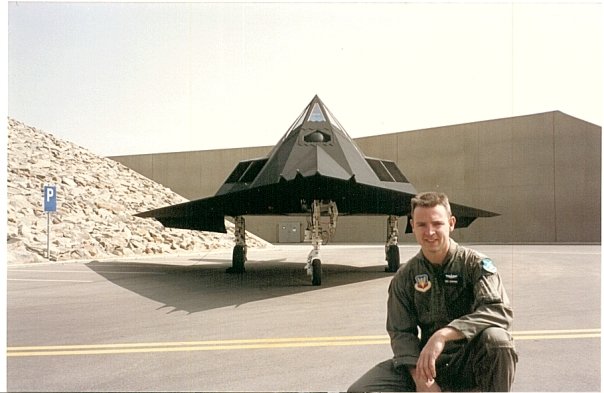

This is the F-117 Stealth Fighter. Officially, the Air Force called it The Nighthawk. Those of us who flew it called it The Black Jet.

This is the first image of the F-117 shown to the public. When the Pentagon released this photo on November 10, 1988, the stealth fighter had already been flying – through its testing and development phases – for over ten years. The 4450th Tactical Group became operational in October 1983, five years before the public saw this photo. Notice how similar this image is to the previous one, other than being deliberately out of focus, and taken from a perspective that makes the jet appear wider than it is long, which is not actually the case.

Here is a photo of an F-117 in sharper focus, taken from alongside. Note the clean angular lines. Except for those antennas on the underside of the jet. More about antennas in a moment.

Here is another view of the F-117 from above. In this photo, you can see the airplane’s arrowhead shape. The four needle-like points at the nose of the airplane are pitot tubes that measure air velocity and static pressure. You can also clearly see the five glass panels of the cockpit. At the back of the plane, what appear to be two white stripes are actually Space Shuttle heat shield tiles used to cool the heat signature of the engine exhaust.

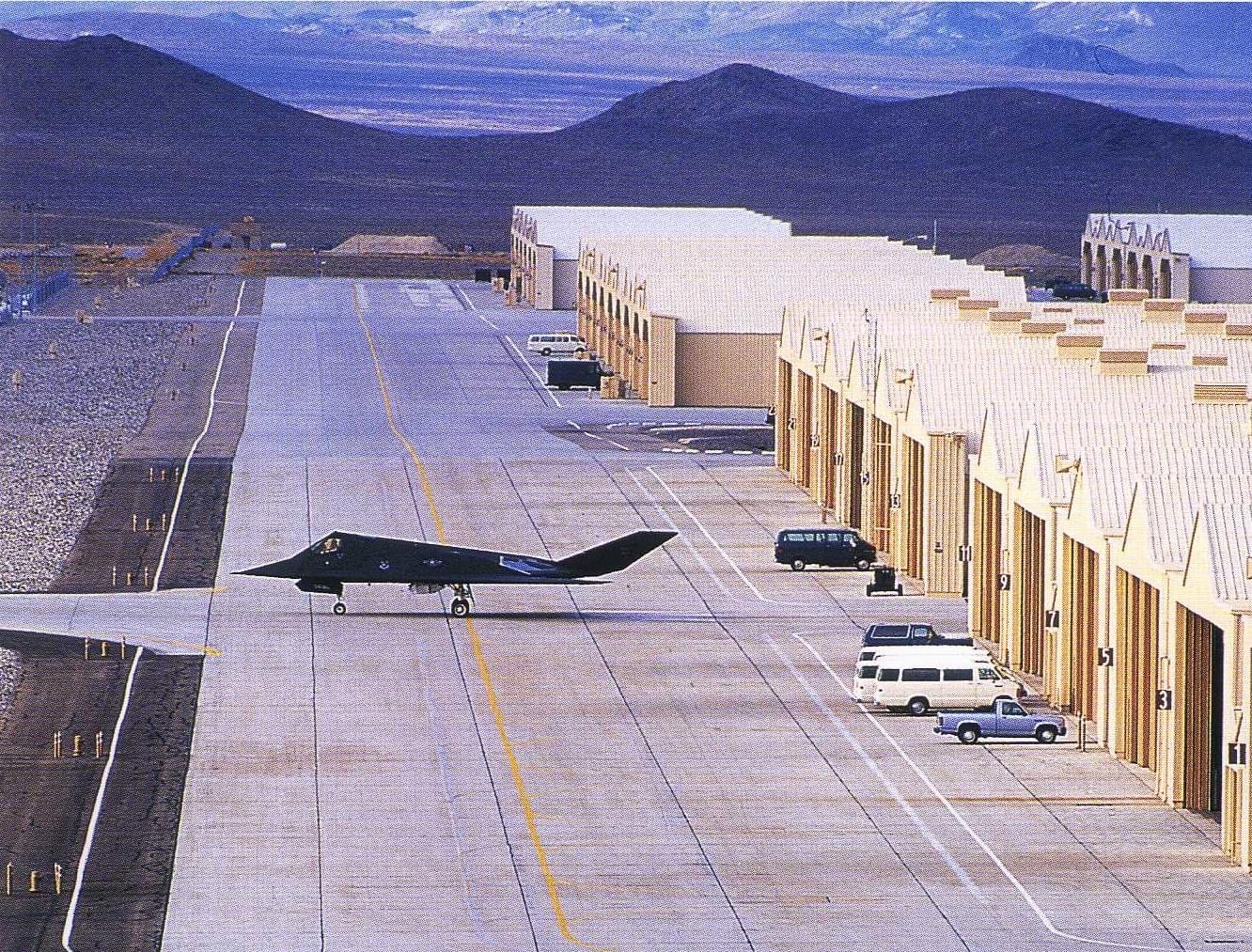

In this photo you can see how the airplane was first revealed to new personnel involved in testing, maintaining, or flying the F-117 during the years when the plane’s very existence was still Top-Secret. At night, on the flightline, with armed security, they would open the hangar doors to reveal “the asset.”

This is the patch of the 4450th Tactical Group. During the 1980s, while the F-117 program was still highly classified, you would see F-117 pilots at the Nellis Officer’s Club wearing this patch, although not their squadron patches, which they made sure to leave in their lockers at a secret airfield “up range” in the Nevada desert.

This photo, taken at Holloman Air Force Base in 2006, gives you a sense of the jet’s scale. The shadow of the jet shows you the arrowhead shape of the plane. Just behind the white Air Force rondel on the side of the jet, you can see what looks like a bump. This is one of two radar reflectors we flew with in peacetime so air traffic control could see us on radar. When we took the jet to war, we removed those, along with a red beacon on the underside of the jet. The beacon was another peacetime concession to non-stealthiness to make the plane more visible to other jets in the night sky.

Here you can see the airplane’s antennas on both the top side and bottom side of the airplane. Antennas extended like this can be picked up by certain types of radar. Thus, when we flew in combat, we retracted these antennas inside the airplane, so they no longer extended as they do in this photo. When we retracted our antennas*, of course, it meant we could no longer transmit or receive on the radio. Which meant, in combat, we often flew radio silent not just out of good discipline, but necessity. [*Note: a modification in the late 1990s added flush-mounted antennas with limited range, but some capability to monitor the air battle underway while we were “stealthed up”.]

Here you can see the apex light above the cockpit, even more clearly. Also notable about this photo is that Thad Darger, Bandit 528, is actually flying the jet with his name painted on the canopy rail.

Note here the flat underside of the airplane. This is intentional so that, as the F‑117 approaches its target, it presents the flat underside, and the sharp arrowhead shaped nose, toward the target area. These are the two portions of the airplane with the lowest radar signature. Also, in this photo, look at the peak of the canopy. You will see a little triangular notch at the top of the canopy that extends just above the airplane’s spine. This is the “apex light” which shines backward, behind the plane, to illuminate the top of the jet during night air refueling.

F-117 flying low level through a mountain pass

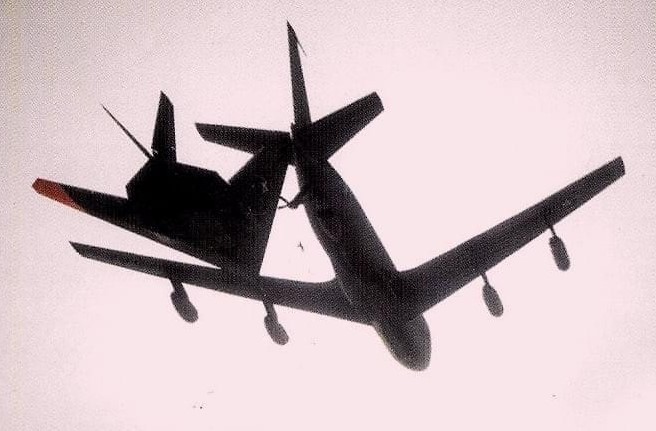

Here you can see the air refueling “boom” extended toward an F-117, ready to connect in midair. You can see the F-117’s air refueling receptacle. It is just behind the cockpit, on the spine of the airplane, and looks like a white square in this photo.

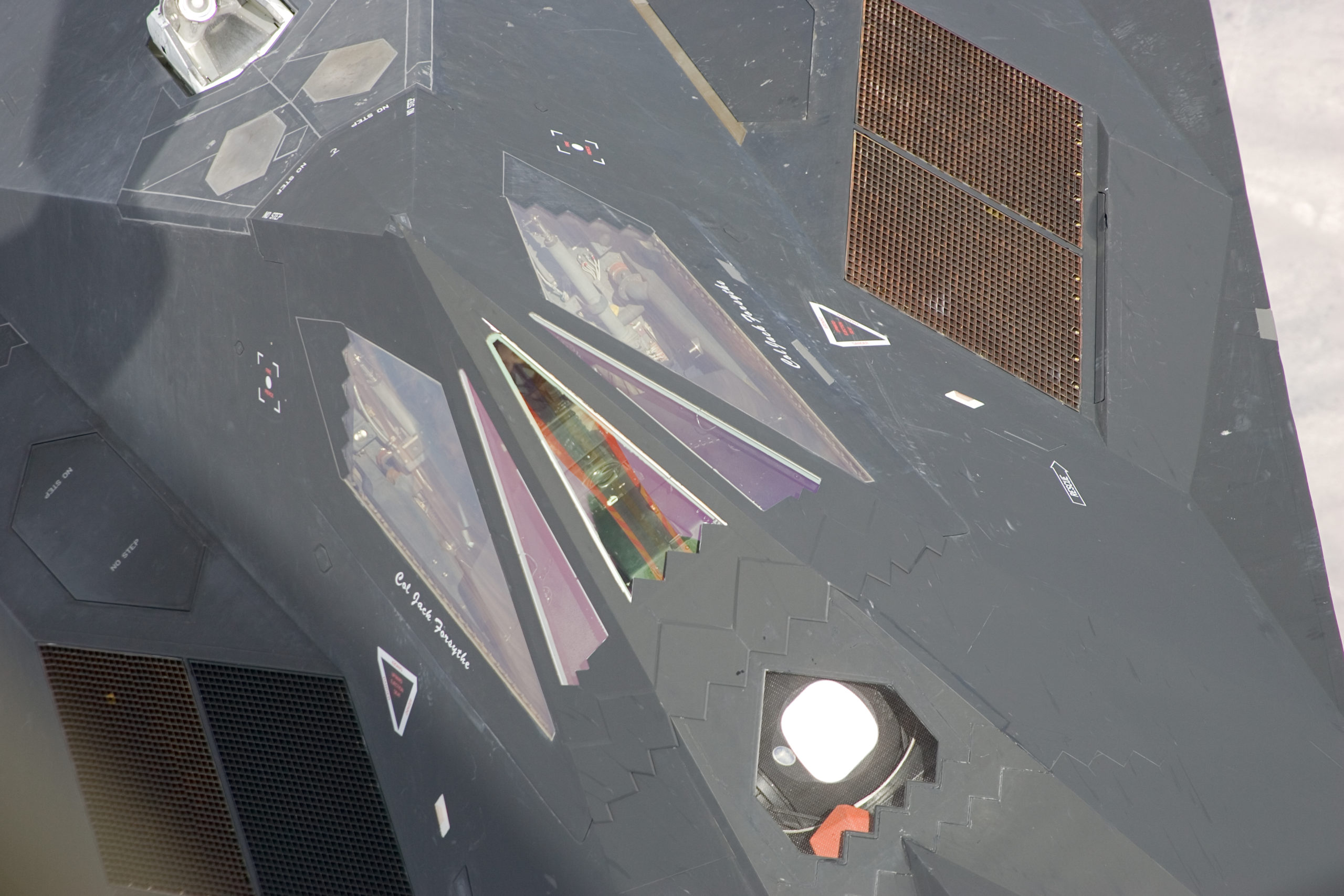

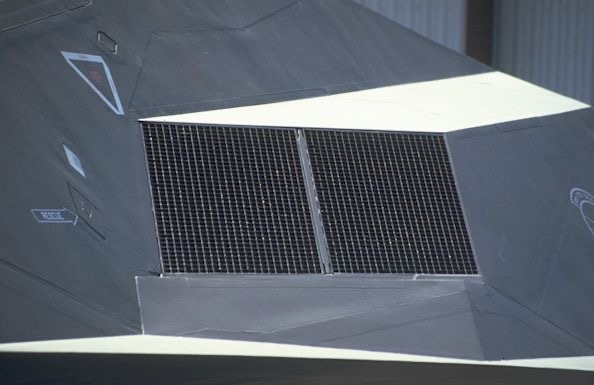

Here is a closer view of the air refueling process. You can easily see the air refueling receptacle, and how close the two planes have to fly next to each other while the process is underway. On either side of the F-117 cockpit, you see two dark trapezoid shapes. These are actually the engine inlets. They are covered with a metal lattice, known as “the ice cube trays.” Each opening in the lattice is no larger than about an inch square. Smaller, in other words, than the radar resolution cell of a target tracking radar. Thus, the air flows through the holes of the “ice cube tray” but the image the lattice presents to radar is of a flat facet, like the rest of the plane’s angular exterior. The reason we do this is to hide the fan blades of our engines, which would otherwise present a large radar cross section to an enemy radar.

A view of the cockpit from above.

In this view you see the perspective from underneath a KC-135 tanker aircraft and an F-117 in the process of air refueling.

Here you see a pair of F-117s with their position lights illuminated. You can even see the apex light on the lead aircraft, just above the cockpit. You can also see an antenna extended on the underside of the lead plane.

Here is the business-end of the F-117. In this photo you see a “dual door” release, meaning the pilot has released two weapons mere fractions of a second apart. These are GBU weapons – the acronym stands for “Guided Bomb Unit.” These are precision guided by the pilot, who aims a laser at the intended impact point. The fins at the front of the GBU guide it to the reflected laser energy shining off the target. The fins at the back stabilize the flight of the weapon, extending their wingspan to over six feet in diameter once the weapon leaves the bomb bay. In this photo, you can see the rear tail fins beginning to extend on the first bomb. The weapons shown in this photo each weigh 2,000 pounds. They are painted blue, meaning they are inert – made of cement. Live weapons made of high-explosive tritanol would be painted green. In this photo, you can also see the open bomb bay doors on the underside of the F-117. Not surprisingly, the radar cross section of the airplane increases dramatically when the bomb bay doors are open. So, we keep the “door open time” to a minimum: just a few seconds to open, release, and then close again.

The green color of this weapon indicates an actual “live” weapon. Note the saw teeth at the front and back of the bomb bay door in this photo. The saw teeth are designed to break up the potential radar return of an object aligned perpendicular to the flight path. You will see saw teeth on the front edge of the canopy as well, for the same reason.

Here is a photo of the underside of the F-117 with the bomb bay doors open.

This photo of the F-117 was taken from the cockpit of a T-38 flying alongside. Just in front of the cockpit, you can see what looks like an inset glass mirror. This is the Forward-Looking Infrared Sensor – the FLIR – in acronym-speak, that enables the pilot to “see in the dark.” There is another Downward-Looking Infrared Sensor – the DLIR – on the underside of the airplane’s nose, as well. Together the FLIR and DLIR enable the pilot to use infrared to acquire and then track the target until impact. Photo credit: Major Jay Doerfler.

4-ship in fingertip formation

Here is the F-117 shown from behind. You can see one of the radar reflectors on the top left side of the airplane. You can also see contrails forming on the leading edge of the wings, meaning the plane is in a hard turn.

This is a simulated photo of a model (not a real airplane) showing a rendering of an F-117 coming in to land with its landing lights on. Even though it’s just a model, I kind of like the photo. Amusingly, it depicts the “ice cube trays” as being illuminated from within, and the Air Force Rondel. Which is another reason you know this is a model. That and the fact that the background horizon is too angular, and the jet itself too clean. But it’s still a cool image.

After landing an F-117 the pilot usually deploys a drag chute, like the one shown here, to help slow down. The F-117 has no speed brakes or flaps, which means you have to land at high airspeeds: above 140 knots (i.e., about 160 miles per hour). There’s also an emergency tailhook at the back of the plane, concealed behind an explosive panel so that, if you have to take an arresting cable to help bring the jet to a stop, you can blow the panel, drop the hook, and catch the cable.

This is another photo with some interesting details. Notice the FLIR screen in the nose of the jet. In Have Blue Sky, one of the civilian characters (a female reporter who embeds with the F‑117s during Desert Storm) will say it reminds her of a “Magic 8-Ball” from when she was a kid. One other thing to note in this photo is that just above the “ice cube tray” you can see one of the open “blow in doors.” This is a design technique Lockheed borrowed from a Russian MiG fighter. At slow speeds the blow in doors open to let more air into the engines. Once the airplane accelerates above ~200 knots (.55 Mach), the air coming into the engines through the ice cube trays is sufficient, and the blow in doors automatically close. When they do, they sound like someone dropping a tray in the kitchen of a restaurant. They usually “bang shut” right after takeoff, not the moment a pilot wants to hear a strange sound.

Dragon Test Aircraft #835, flown by Joel Rush, Bandit 463.

You can see a number of interesting details in this photo, as a weapons load team uses a jammer to load a bomb into the left bomb bay. One detail is the metal plate (painted white) and filled with circular holes that makes it look like a piece of Swiss cheese. These plates extend downward any time a bomb bay door is open (even when the jet is on the ground). In flight, they disturb the airflow below the bomb bay so that a weapon does not hit a solid wall of air and bounce back up into the bomb bay after release.

Another detail are the three landing lights (one on each of the main landing gear, plus the nose gear. This “non standard” configuration (most USAF jets have only one or two landing lights) was part of the original deception plan. If anyone ever saw three landing lights officials could explain it away as being a civilian King Air.

To the left side of the photo you can see the red rotating beacon (an item removed in wartime) and just above it the “Downward Looking Infrared” (DLIR) sensor, which the pilot uses during the final moments to guide a weapon to its target.

417 Weapons School live load at Nellis AFB, Nevada

A crew chief marshalling an F-117 out of one of the flow-through hangars at Holloman.

Here is a close-up view of the “ice cube tray” over the left engine inlet.

Two things I want to point out in this photo. One is the gold-colored glass of the canopy, which you can see especially well in this photograph. That is a treatment to prevent a radar return from the cockpit itself. The second thing to observe is the way the elevons at the back of the left wing are drooping like barn doors. This is because the plane does not have the engines running and thus hydraulic power going to the elevons to make them streamline with the wing.

Here is the cockpit of the F-117. This photo reminds me of an insect stuck on a pin inside a box: technically correct, but hardly alive. What you don’t see in this picture is the Infrared Acquisition and Designation System – the IRADS display – which is the infrared picture of the outside world, displayed on the big center screen. You also don’t see the heads-up-display. The righthand multi-function display is normally set to show a moving map. Here, all we see is a compass rose. Which is not a mode you would usually fly in. You can just make out the green lettering of the screen of the Inertial Navigation System – the INS – on the lower right instrument panel. If I had to guess, I would say this is probably a photograph of the F-117 cockpit simulator. All in all, a somewhat lifeless, if technically accurate, photo.

Here is a better photo of the cockpit, although without power on, so none of the glass panel instruments are displaying data.

Three F-117s climbing into the sunset.

Between 1982 and 1990, the Lockheed “Skunk Works” delivered 59 F-117 Stealth Fighters to the U.S. Air Force.

This is the windowless hangar in Burbank, California, where the Stealth Fighters were constructed.

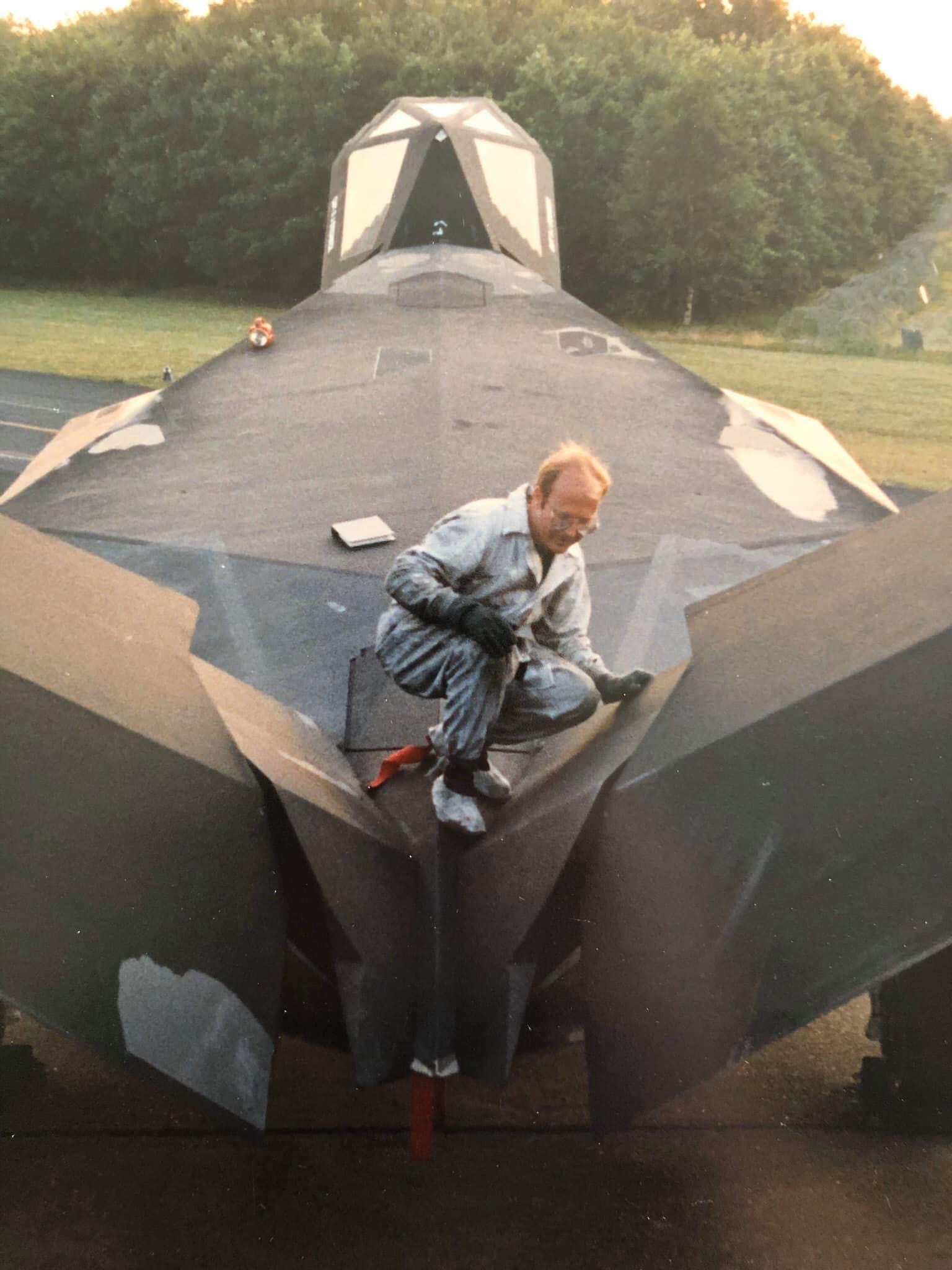

Here you can see a closer view of an F-117 under construction. The yellow skin of the airplane results from coating the aluminum skin with Zink Chromate, a chemical which essentially serves as a primer. It protects the aluminum by reacting to corrosion first, before the aluminum does. This is a process used in airplane manufacturing since the 1940s. Lockheed covered the aluminum skin of the F-117 with radar absorbent material, which looks like gray linoleum when applied. The black exterior paint was then applied over the RAM material.

The aft section of an F-117 under construction.

An F-117 stealth fighter begins to take shape.

After construction, each F-117 was flown (with its wings removed) to an air base in Nevada. This photo is more recent, showing a disassembled F-117 being flown to an air museum. During the original missions in the 1980s the disassembled airplanes were covered in black plastic to disguise the identity of the cargo. The crews who flew the transport planes referred to these secret deliveries as “black plastic missions.”

Col Shelby Cordon(RM), MGen Joe Ashy, Secretary of Defense Frank Carlucci, and Col Tony Tolin. In the background is one of the Key Air airliners used to transport personnel to and from bases up-range.

The secret F-117 base at Tonopah Test Range, Nevada.

Here is a photo of the first two F-117s landing at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada for the public unveiling of the stealth fighter on April 21, 1990. The public unveiling serves as the backdrop for one of the chapters in the novel Have Blue Sky.

Joe Salata, Bandit 295, at the Dayton Airshow in the early summer of 1990.

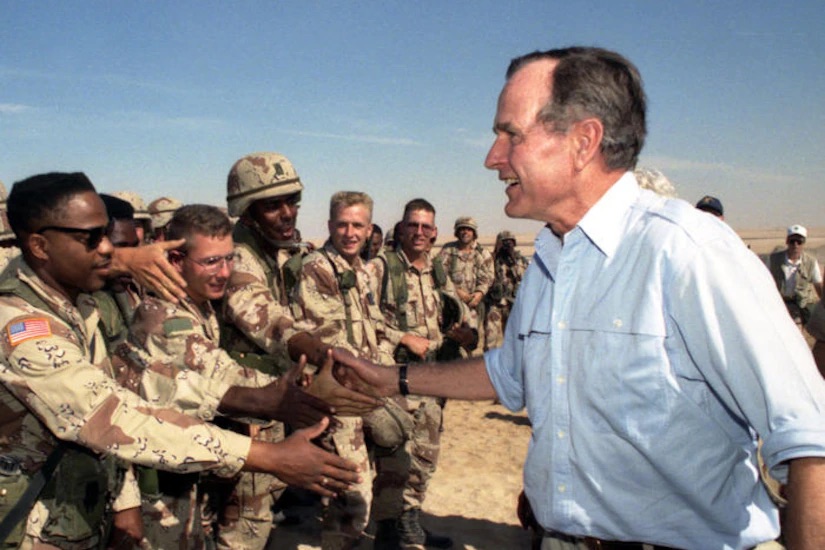

On August 7, 1990, President Bush initiated Operation Desert Shield in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. Six days later, on August 13, 1990, one of the two squadrons of F-117s based at Tonopah Test Range – the 415th Nightstalkers – got orders to deploy to Desert Shield.

Here you can see the Nightstalkers on their way to the Persian Gulf, as they stop at Langley AFB in Virginia, before making the cross-Atlantic, cross-Mediterranean flight the next day. What is notable, but not apparent, in this photo is that all the jets are fully loaded with bombs. At the time, they didn’t know what combat provisions they would find on hand when they landed in Saudi Arabia. So, the Nightstalkers took one mission’s-worth of firepower with them as they flew halfway around the world to their destination: an airbase in southwestern Saudi Arabia near the city of Khamis Mushait.

President Bush visiting Saudi Arabia during Desert Shield.

In November 1990, a second squadron of F-117s – the 416th Ghost Riders – got orders to send an additional 24 F-117s to Saudi Arabia. Several chapters in Have Blue Sky describe the missions flown by the F-117 pilots during Desert Storm.

Here you can see the underground shelters used to protect the F-117s at Khamis Mushait.

The F-117s during Desert Storm “owned the night” as the patch says. But this does not mean (despite the official story at the time) that they came through the war without a scratch. That is another story you can read about in Have Blue Sky – one we are finally able to tell 30 years later.

In 1992 the F-117’s at Tonopah moved to Holloman AFB in southern New Mexico, and became part of the 49th Fighter Wing. The Latin motto “Tutor et Ultor” means: “Protect and Avenge.”

President Bush’s popularity after Desert Storm, as measured by Gallup, reached 89% — the highest of any president since Gallup began measuring presidential popularity. Over the last two years of his term, however, Bush’s popularity ebbed, dropping as low as 29% during the months the F-117s were relocating to Holloman. Bill Clinton won the presidential election in 1992, and a few months after he became president, Clinton lifted the exclusion against women serving in combat. In Have Blue Sky the character of Eve Riley graduates from pilot training just as the restriction against women serving in combat is lifted.

On September 14, 1997, Major Bryan “BK” Knight, ejected from his F-117 during an airshow at Glenn Martin State Airport when the left wing of his aircraft broke off. In this photo you can see the canopy of Bryan’s jet has separated as part of the ejection sequence. The bright flame is the rocket motor of the ejection seat. Bryan landed under his parachute less than 100 feet from the fireball.

I flew the A-10 Warthog for the first 10 years of my flying career in the Air Force. The first time I flew the F-117 was on December 15, 1997. When they inducted me and the other three pilots in my training class into the Bandits, I became Bandit 534.

When the commander of the 7th Fighter Squadron presented us with our bandit coins, he also presented us with a small lapel pin, telling us: “Back in the day when the existence of the program was still a secret, each pilot who flew the Nighthawk received one of these silver lapel pins. This ruby-eyed Nighthawk pin was the only artifact an F-117 pilot could wear that indicated the plane they flew.

“Casual Friday” to a fighter pilot means wearing an unofficial squadron patch, like this one….

…and a Friday nametag, like this one, with your callsign.

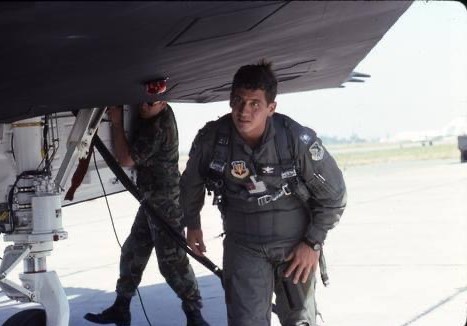

On March 19, 1998 – three days after I finished my checkout in the F-117 – I deployed with the 9th Fighter Squadron Iron Knights to Kuwait. The F-117s and other fighter units had been called to the Middle East in response to Saddam Hussain latest round of saber-rattling. We flew missions in Kuwait for the next three months, returning to Holloman that June. In the fall of 1998, less than a year after my first flight in the F-117, and exactly one month after I pinned on the rank of lieutenant colonel, I became the operations officer (i.e., the second in command) of the 9th Fighter Squadron Iron Knights.

On February 20, 1999, our sister squadron – the 8th Fighter Squadron Black Sheep – deployed 18 stealth fighters to Aviano Air Base, in northern Italy, to support the possibility of an armed conflict with Serbia. On March 24, 1999, Operation Allied Force began. On the fourth night of Allied Force, the Serbians shot down an F-117.

You can see the wreckage in this photo. The pilot, Dale Zelko, was successfully rescued later the same night.

In this photo, you can see the tail number of the jet, #806, and the Holloman identifier “HO.”

After the shootdown of the F-117, the Pentagon ordered the Iron Knights to join the air battle over Serbia. On April 3, 1999, we deployed 19* jets to Spangdahlem Air Base in Germany. For trivia experts: 9th EFS on this patch stands for “9th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron.” [*Note: Once we got to Spangdahlem, we sent one jet on to Aviano to replace the jet that had been shot down.]

In this photo you can see one of the Iron Knight jets landing at Spangdahlem. Less than 36 hours later, we were dropping bombs on Serbia. Several chapters in Have Blue Sky describe the experiences of both the Black Sheep and the Iron Knights during the 78-day bombing campaign against Serbia.

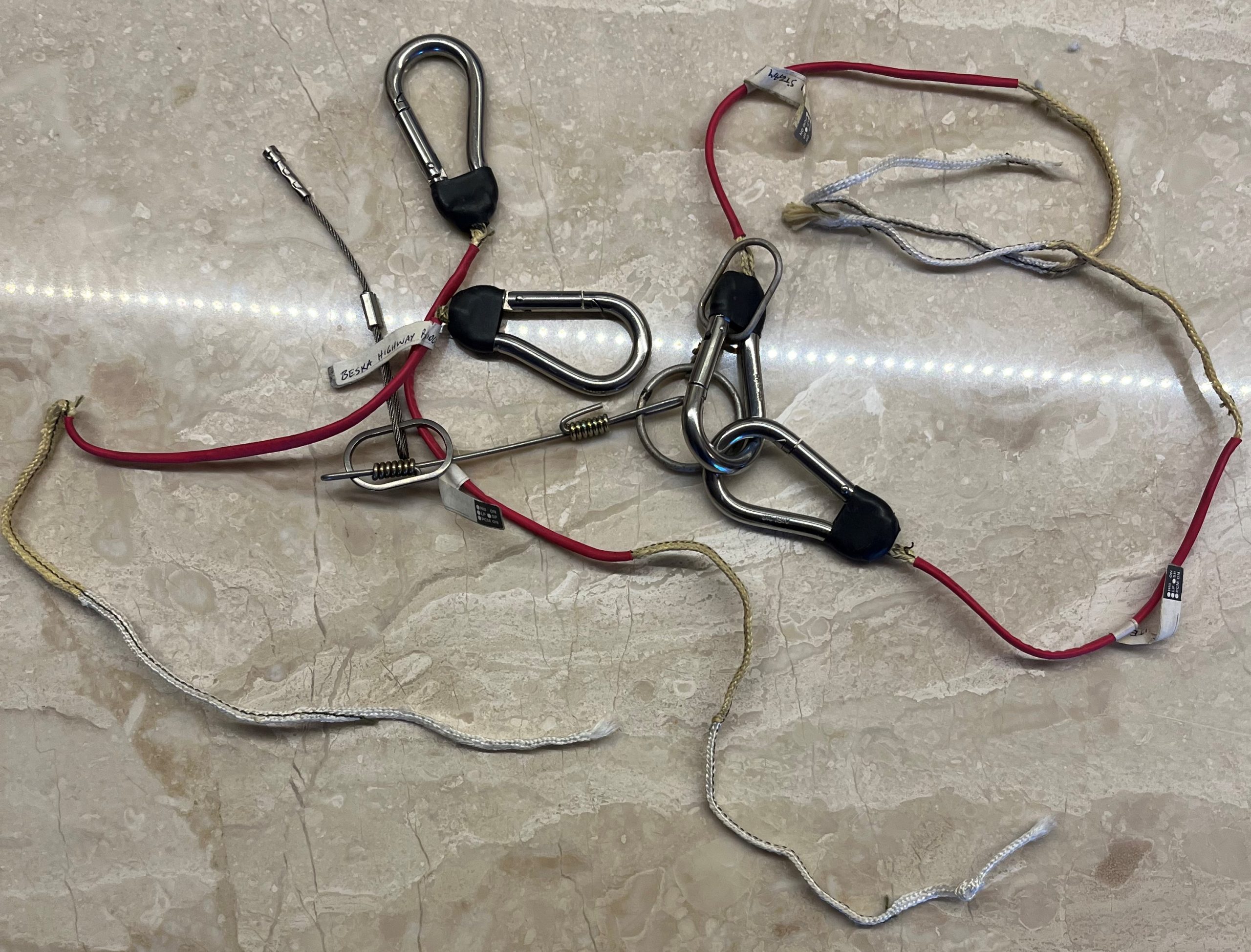

When we came back from our combat missions over Serbia, we saved the wires left hanging in our bomb bays that armed our bombs when they released.

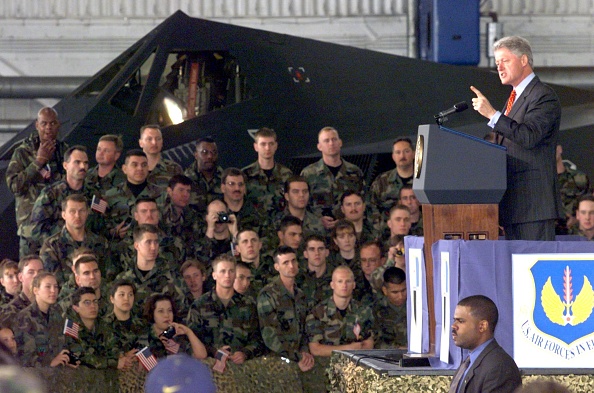

In May 1999, at the height of Operation Allied Force, President Clinton visited Spangdahlem. You can see him here addressing the troops in front of an F-117. Just before this photo was taken, the president visited the Iron Knights squadron operations, and we showed him a “greatest hits” tape of our attacks downrange in Serbia.

In June of 1999, when the F-117s returned from Operation Allied Force, I became the squadron commander of the 8th Fighter Squadron Black Sheep.

The Black Sheep in formation between the rows of hangars known as “The Canyon” at Holloman AFB.

Here is a photo of an F-117 flying over “The Canyon”.

As the Black Sheep commander, I took an F-117 to several airshows, including this one at Oceana Naval Air Station in Virginia Beach. Here you can see the F‑117 and the B-2 – angular stealth and smooth stealth – parked side by side.

At airshows we would “rope off” the F-117 so that the public could see the airplane, but not get too close.

This photo shows several aircraft on “static display” at McEntire Air National Guard Station, South Carolina.

This photo was taken a few miles to the south of Holloman, over the dunes of White Sands National Monument.

And here a two ship at sunset.

After the Black Sheep, they sent me to Air Force Headquarters at the Pentagon.

I was in the Pentagon on 9/11. One of the chapters in Have Blue Sky describes what we experienced on the day of the attack.

I returned to Holloman in 2005 as the Vice Wing Commander, and for six weeks as the wing commander, during the interregnum between the departure of Brigadier General Kurt Cichowski, and the arrival of the new commander, Brigadier General Dave Goldfein.

In this photo you can see Brigadier General Dave Goldfein taking the command guidon from the 12th Air Force commander, Major General Norm Seip.

On October 27, 2006, to celebrate the twin milestones of 25 years of flying the F-117, and 250,000 flight hours, we flew a 25-ship-formation of F-117s over Holloman Air Force Base.

The jets taxiing out for the takeoff of the 25-ship. Yes, I am the knucklehead who turned his landing lights on too early.

I am #22 of 25 in this photo, flying the inside left-wing position in the last element of the 25-ship.

The week after the 25-ship flyby, we began retiring the F-117s. Over the next two years, a handful of F-117s would take their last flight each month to Tonopah Test Range, gradually drawing down the fleet of Stealth Fighters at Holloman. They would be replaced by F-22 Raptors.

On April 21, 2008, exactly eighteen years to the day after the public unveiling of the F-117 in 1990, Colonel Jack “Ripper” Forsythe led the last 4-ship of F-117s from Holloman to the Lockheed plant at Palmdale, and then to Tonopah Test Range where the jets would be placed in mothballs. They painted the underside of Ripper’s jet with the stars and stripes.

Lockheed test pilot Bill Park flew the first test flight of the Have Blue Proof of Concept Demonstrator on December 1, 1977.

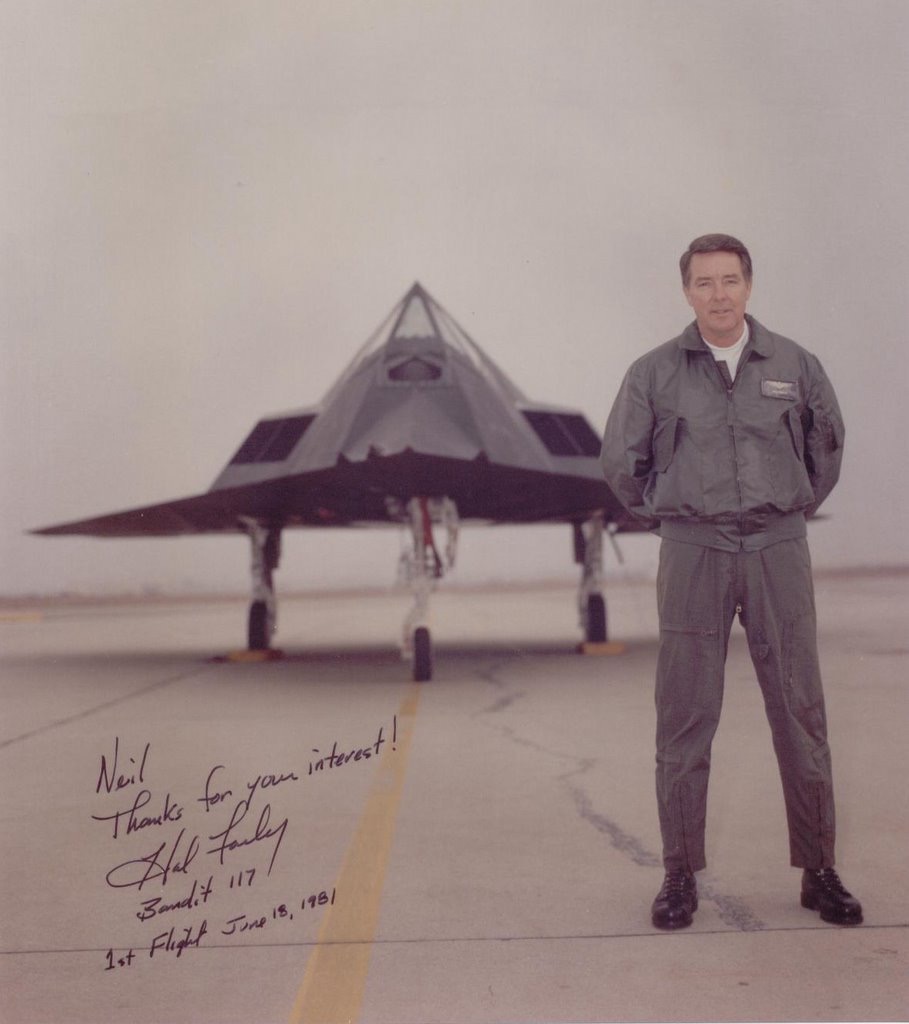

Lockheed test pilot Hal Farley, shown here, flew the first test flight of the F-117 “Senior Trend” aircraft on June 18, 1981. Hal Farley’s Bandit Number is #117.

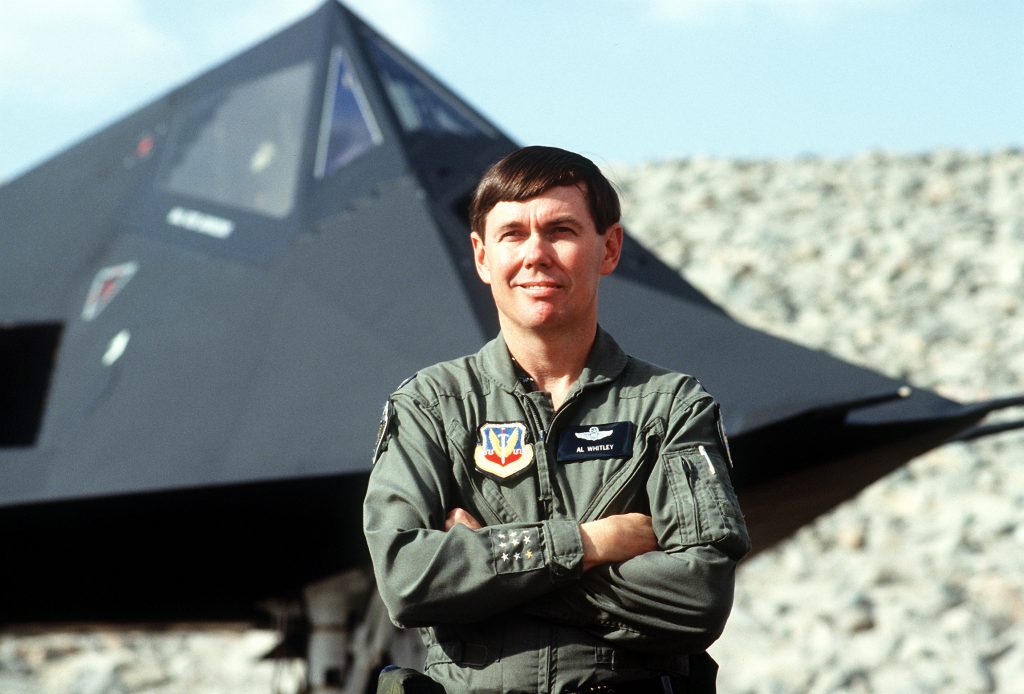

After Lockheed delivered the F-117s to the Air Force, we started numbering the Bandits at #150 to keep the actual number of pilots flying the jet a mystery. Al Whitley, shown here, became Bandit 150, flying the first “operational” F-117 on October 15, 1982.

The last “operational” Bandit was Dave Goldfein, Bandit 708, shown here.

You will see additional Bandits below. Please note that they are not shown in sequential order. Rather, I have added them below as their photos have become available.

Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168, shakes hands with Colonel Milan Zimer, Bandit 169, on the occasion of his F-117 fini-flight in July 1986.

Joe Salata, Bandit 295, commander of the 9th Fighter Squadron during Allied Force.

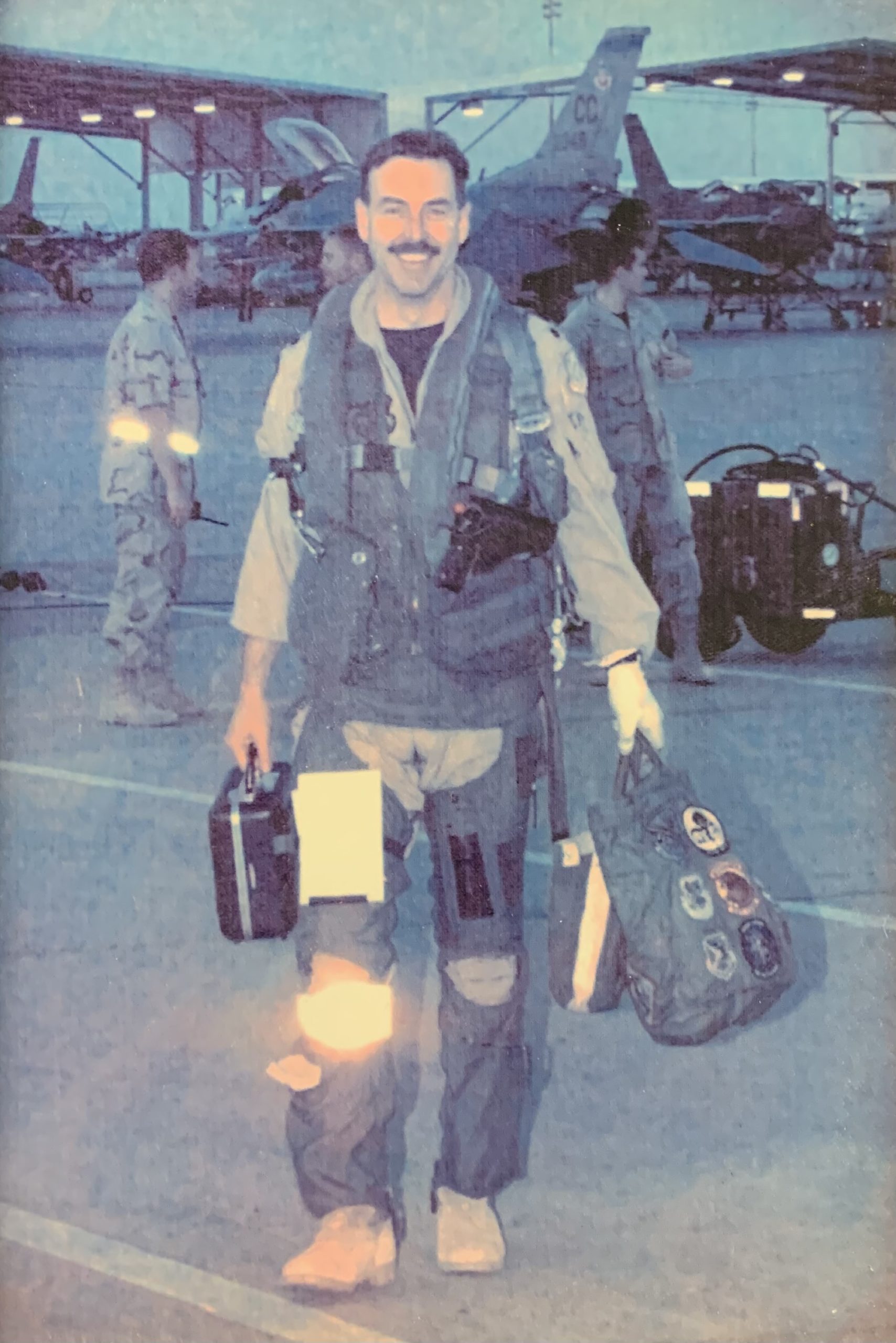

Rich “T-Pup” Treadway, Bandit 336, on the flight line at Al Jaber Air Base in Kuwait: April 1998. In this photo, taken at dawn just after he landed, you can see Treadway carrying his EDTM and helmet bag, with a holstered pistol in his survival vest. At the time of this photo he was the Operations Officer of the 9th Fighter Squadron. He later went on to command the 49th OSS.

Chandra Beckman, Bandit 680. Photo credit: Caliaro Luigino.

Michael P. “Chip” Setnor, Bandit 217. First flight in the F-117. October 21, 1986. Location-Data Masked. Also pictured, at left: Tim Sims, Bandit 192. Center Foreground: A-7D chase pilot, Harry Greer.

Chris Knehans, Bandit 633, commander of the 7th Fighter Squadron and overall flight lead for the 25-ship flyby on October 27, 2006.

Al Whitley, Bandit 150; Bob Maher, Bandit 308; and Steve Charles, Bandit 263, at Langley AFB, December 1990.

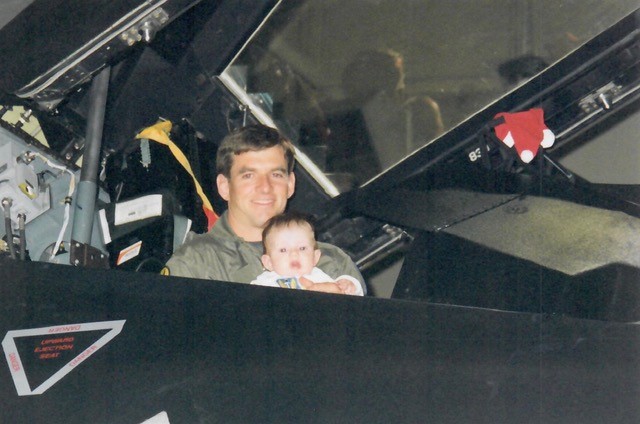

David Moore, Bandit 534, at Holloman AFB, February 2007.

Randy Eckley, Bandit 458, who later commander the 49th OSS. Holloman AFB, 1994.

Gary Woltering, Bandit 454, commander of the 8th Fighter Squadron, at Al Jaber Air Base, Kuwait, 1998.

Mike Roller, Bandit 453, at Al Jaber Air Base, Kuwait, 1996.

Angelo Eiland, Bandit 364.

Christina Szasz Beck, Bandit 671.

Braden Delauder, Bandit 424, with his son Christopher, age 4. July 1995.

The Black Sheep pilots at Aviano Air Base, Italy, during Operation Allied Force. April 1999.

Lee Wyatt, Bandit 517, and Chip Rice, Bandit 518, at the operations desk getting ready to step to fly on the first night of Operation Allied Force.

Batajnica Airfield, Serbia.

David Gossett, Bandit 669.

Larry Guichard, Bandit 541.

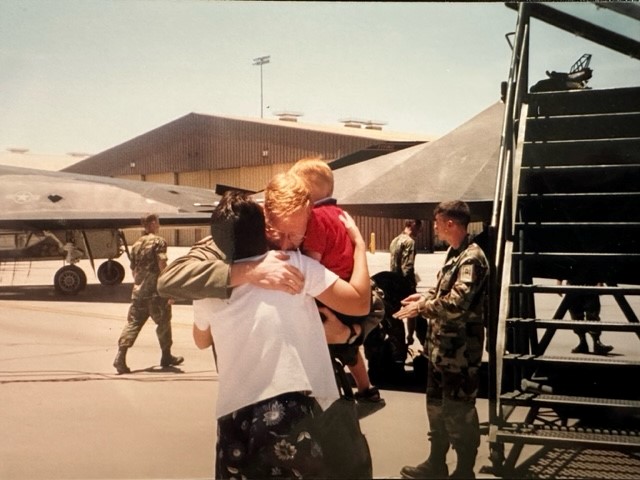

Operation Allied Force Homecoming — June 1999.

The leadership of the Stealth Fighter Association at the 40th Anniversary Stealth Fighter Reunion in 2022: Phil McDaniel, Bandit 306, Tnle McCloskey, and Rick Wright, Bandit 352.

F-117 RTU classmates: Dan Gruber, Bandit 455; Gary Woltering, Bandit 454; Mike Roller, Bandit 453; and Curt Cichowski, Bandit 452.

Greg Feest, Bandit 261, Tnle McCloskey, and Joe Salata, Bandit 295, at the 40th Anniversary Stealth Fighter Reunion in 2022.

Tom McCloskey, Bandit 478, Al Jaber Air Base, Kuwait, 1998.

Tom McCloskey and co-pilot.

Thad Darger, Bandit 528, pre-flighting his jet prior to a combat mission. Aviano Air Base, Italy, April 1999.

Dave Shipley, Bandit 501.

John Jozwicki, Bandit 559.

Greg Sembower, Bandit 351, at Khamis Mushait.

A Friday evening gathering of the 9th Fighter Squadron Iron Knights.

Squadron collection of Black Sheep nametags.

The 7th Fighter Squadron “Bunyaps” in 2002.

Braden Delauder, Bandit 424; Todd Flesch, Bandit 447; Ken Tatum, Bandit 527; Mark Drinkard, Bandit 404; Joel Rush, Bandit 463; and Angelo Eiland, Bandit 364.

George Kramlinger, Bandit 552; John Snider, Bandit 529; John Good, Bandit 556; and Joe Skaja, Bandit 411.

417th Weapons School Initial Cadre: Clint Hinote, Bandit 567; Todd Emmons, Bandit 563; Mark Hoehn, Bandit 554; Tom Shoaf, Bandit 358; and Phil Taber, Bandit 576.

Weapons School students, instructors, and staff, with Denys Overholser — whose name appears on the patent for the F-117.

Phil McDaniel, Bandit 306 in 1991.

Chris Babbidge, Bandit 474; and Ken Dwelle Bandit 475.

Mark Perusse, Bandit 497, on the first night of Operation Allied Force.

Phil Tabler, Bandit 576, Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003.

Brig Gen Dave Goldfein presents 1000 hour Nighthawk Trophy to Lt Col Ken Tatum

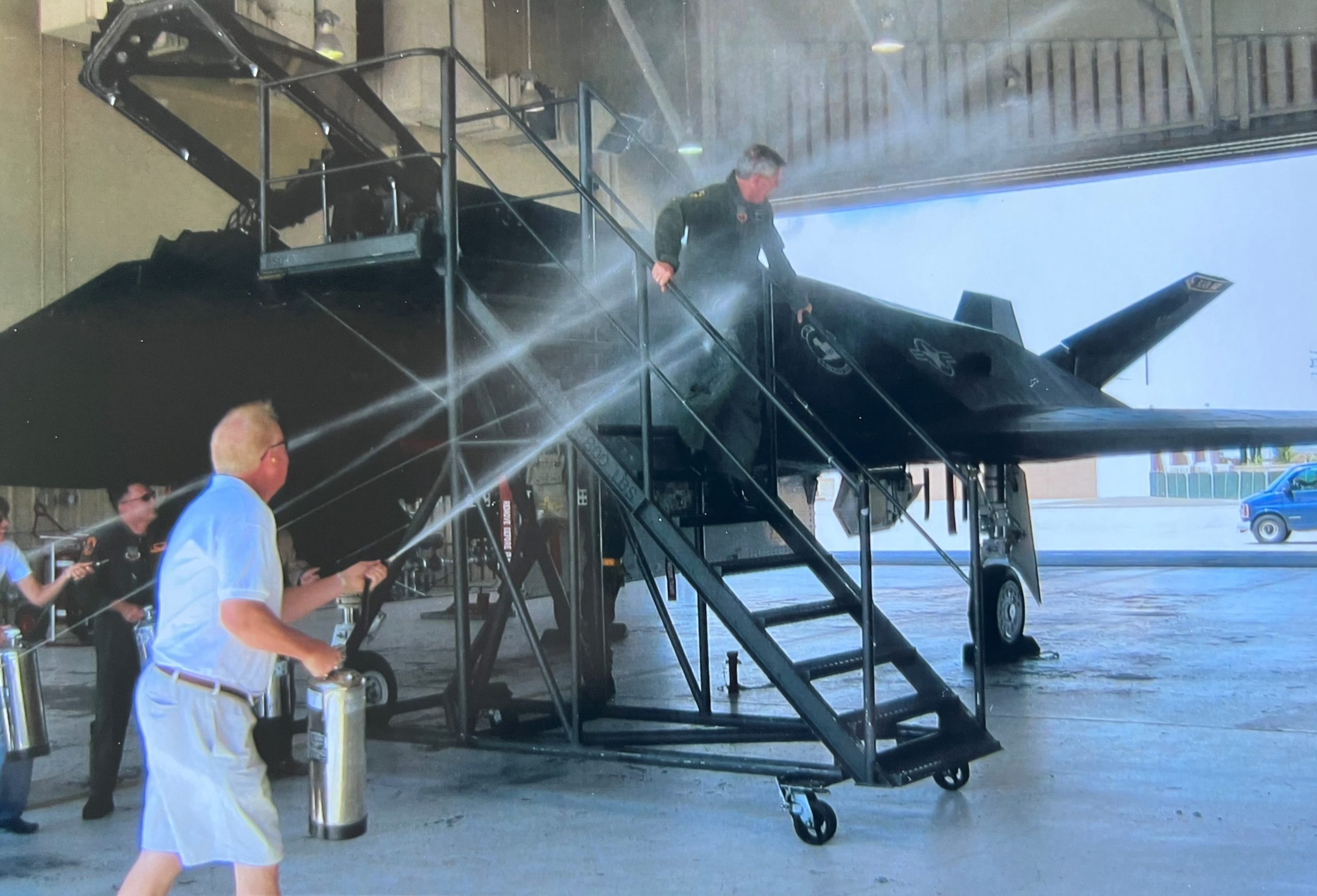

David Moore, Bandit 534, fini-flight in the F-117, July 6, 2007.

SSgt Greg Auzenne of the 8th Fighter Squadron marshalling aircraft 803. Holloman AFB. August 15, 1996.

SSgt Robin Walker, with a flashlight, is getting ready to inspect the engine by accessing the blow-in-door. SSgt Greg Slavik is speaking to him from the cockpit. Photo credit: TSgt Kevin Gruenwald.

SSgt Anthony Hyland (L) & TSgt Eric Brennon (R) prepare to open the engine bay.

Here a “Martian” works between the tails of the F-117 sanding the radar absorbent material that covers the exterior of the jet. The nickname “Martian” stems from both the name of the maintenance section where they work – the “Material Application and Repair Section” — and from the Martian-like suits they wear when working with the radar absorbent material.

SSgt Yancy Mailes with a GBU-27

MSgt Keith Hilton, SSgt Yancy Mailes, and SSgt Rocky Tinsley during the early testing of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM)

Desert Storm Red Recovery Crew

Maintainers at Khamis Mushait

F-117 undergoing maintenance

F-117 Air Demonstration Team at RAF Fairford in July 2007

Marshalling in a Black Sheep jet

On the ramp at Nellis AFB

Crew Chief Romeo Casuga under Aircraft 817

Benny Ontiveros at Al Jaber Air Base in Kuwait

Members of the 8th Fighter Squadron at Al Jaber Kuwait with the damaged aircraft shelters in the background from Desert Storm.

Security Forces in front of the Black Jet.

F-117 Crew Chief Michael Bodewitz

Maintainer inspecting engine inlet

Jose Lugaro and the original “Lone Wolf”

Larry, Bill Miller, David Schlater, and “The Overachiever”

In front of one of the bat caves at Khamis